I was apprehensive about writing a blog for this academic year. This blog was started in October to explore academic writing in a public online space. Before I even began writing I had a difficulty deciding what I was going to write about. I found my first couple of posts extremely daunting and feared I was not completing them to a high enough standard. However, with my last post on how manga and anime was consumed in 1980’s America, I felt much calmer and reassured in my abilities to write academically while, hopefully grabbing the interest of the reader.

At the beginning of the first semester the class was instructed to choose a theme and begin writing. With my first post, ‘How important is the comic creator to the audience?,’ I find myself particularly critical of the subject matter and my writing ability. I was very nervous that a blog post centered on comics and their creators would be too steeped in the realm of pop culture and would be perhaps, too low brow for an academic blog. Nevertheless, it was a subject I found myself drawn to.

“Finger is now considered by fans to have played an integral role in the development of the Dark Knight. He designed his outfit and his infamous parental death back story. Finger claims that he made Batman into a superhero-vigilante, whereas Kane made him into a scientific detective. He played a major role in Batman’s villains, including the Joker as he scripted his story. Finger was pushed out as he was slow to produce work. He received almost no credit for his contributions until Kane publicly acknowledged him in 1989, fifteen years after his death. Jerry Robinson, who was acknowledged as the artist of the Batman series insisted for years that Finger was a major creator of the Batman series but was largely ignored.”

Since I was very young I have read anything I could find on American superheroes. But, even I had trouble remembering who created characters or even who wrote a particular series’. Comic writers and artists are rarely seen as important to the audience. Almost everyone has heard of the two major American comic companies, D.C. and Marvel, but few have heard of Bill Finger, Jerry Siegel or Joe Shuster. Many people have of course, heard of Stan Lee, but he had to fight numerous court cases to own the rights to the characters that he created. This post caused me to research the legal disputes and question the importance of what many believe, to be a pointless and childish past-time. Even with the praise that Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight Trilogy received, the comics that the films were based on are still viewed as a throwaway and a low brow medium. As odd as it is, the films gained both the critical and mainstream audience’s approval. This was a huge change for comicbook movies, as now they are some of the highest grossing films that are theatrically released. But my interest lay in the comics themselves and how the creators are discounted from any legal or general recognition from the reader. I was not satisfied with my first entry. I felt it was rushed and far too short. We were told to keep our posts less than six hundred words and I strived to do so. But, in the end this was not realistic, as I continued to write my posts got longer and longer.

My second post began the entries on the seminars that I attended. These seminars were hosted by the English Department in UCC and had a variety of subjects to write about. My second entry, Crowdsourcing – Not as Fun as Crowdsurfing, focused on the different ways that crowdsourcing has been used in recent years. This entry required me to research into areas that I had never heard of. I looked at historical examples such as The Longitude Reward in 1714. But the examples from the Japanese Earthquake and Tsunami in 2011 were the most interesting. I have only contributed to crowdsourcing once, to support a game based on a comic and it caused me to questions the legitimacy of different platforms for crowdsourcing.

“It has been seen that social media sites like Twitter have been used in disasters such as the 2011 Japanese Earthquake and Tsunami. Misinformation and false tweets were re-tweeted and caused problems for rescue services during the disaster. A fake tweet calling for help was re-tweeted over 11,000 times. Because of instances like this, the public bodies that handle the coordination of information during crises have to work harder to verify the legitimacy of social media crowdsourced claims.”

I spent hours researching different forms of crowdsourcing and different instances where it succeeded and failed. Most researchers did not show crowdsourcing or croudfunding in a good light. It appears crowdsourcing is, at best cheap and sometimes dangerous. This entry showed some of the many problems that arise when there is no group policing the information that is appearing. I believe that I engaged with this entry far better than my first one, however it still felt incomplete. This is because I was still following the six hundred word recommendation for length. I struggled to find the correct tone for these posts and made quite a few grammar, spelling and punctuation mistakes.

My next post was on the WikiEditathon, which turned out to be really entertaining. The class was told to pick a Wikipedia article and get ready to edit it. This was another moment where I was terrified I would mess up. We even had to live tweet the process. I decided to edit the Wikipedia article on the video game Martian Gothic Unification. This was partly due to recently completing the game. The most obvious reason was because the page was almost empty. When I wanted to get the game there was useful information on the page, which was frustrating. So I edited some parts and added a lot. In the post you can find the original way the article looked and my changes are highlighted with various colours to denote the differences.

“There was no Development section so I created one. I found an interview with Stephen Marley, the writer of the game. He described how the game came about and expressed his disappointment with the final product. I also filled in more information in the Reception section from more reviews that were available. I then fixed the citations and added links to both Wikipedia articles and external pages.”

During another seminar I became interested in censorship in Ireland. I was already immensely aware of censorship in anime and American cartoons. The post, Censorship in Ireland and Abroad, caused me to look at censorship in Ireland far closer. I learned that the State introduced the Defamation Act 2009 and included a blasphemy law. That was both surprising and worrying. However, censorship in Ireland has only affected me once. I have a vague recollection in 2007 of Manhunt 2’s unavailability in Ireland. It is the only video game ever to be banned in Ireland, interestingly, it was never even submitted to the IFCO for review.

This post went a lot off track as I had very little on the seminar in it. But I managed to salvage it in the last paragraph to an extent. The majority of the seminar focused on censorship in the US. The main reason for this was my experience with it. I remember watching these shows and the episodes would be inconsistent. Sometimes Cartoon Network UK would show the American censored version and other times it would be the DVD uncensored one. It made watching Dragonball Z (1989) and Pokemon (1997) a bit confusing as sometimes the characters would die and other times they were just horribly injured. Even in a show like in Yu-Gi-Oh! (2000), an anime about card games, censorship removed all traces of guns, implied death, and strived to “Americanize” all Japanese names so American children would not become confused. My interest in this post became focused on comedy rather than the Dan O’Brien’s seminar.

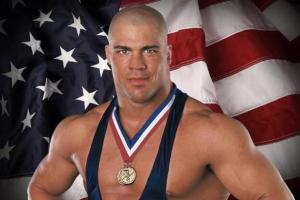

“However, censorship was and still is still globally widespread. For example, in WWE (World Wrestling Entertainment) the term “wrestler” is banned. They are called “Sports Entertainers.” One of these “Sports Entertainers,” Kurt Angle, was an Olympic Gold Medal wrestler.”

It is rather strange to see censorship like this in on American television in 2011. But the sudden changes in WWE was rather humorous as was the removal of blood and references to death in almost show, even when not aimed at children. I forgot about the seminar for the most part and had to try to include it in my final paragraph of the post. I think this post should have focused far more on reacting to the different examples and instances that Dan O’Brien discussed in the seminar on Edna O’Brien’s The Country Girls Trilogy. This post was not detailed enough and did not focus enough on the seminar. But, rather on the more comical instances of censorship that I have experienced.

I think my favourite series of posts during this assignment has been on the consumption of manga and anime in the United States since the 1960’s. I wanted to continue with these posts up until the 2010’s but I could not find the time to do so in the last few weeks. What I have written, however, is interesting in its own right. These posts detail the way in which manga and anime rose to popularity in the US. These were particularly interesting to me as my thesis is focusing on manga and anime, but from the 1980’s and 1990’s. I grew up on manga and anime. Manga was and still is just waiting to be read online for free, the Japanese publishers do not sue the fan translators very often. I remember every weekday after school at five o’clock was Toonami. It was a time slot on Cartoon Network that began in 1997 and ran until 2008. It showcased some of the most popular anime of the late 1990’s, such as Dragonball Z (1989), Sailor Moon (1992), and Naruto (2002). I tried to detail the change in under one thousand words each time. I may have broken this limit often, but all in the name of composing a coherent assessment of the rise of manga and anime.

In 1960’s: How Manga and Anime Was Consumed in the United States, I primarily described the introduction of anime to America in the 1960’s. I was hoping to go into more detail, but I could not find much more information. The introduction of anime to the US was slow and controlled. Only two television anime managed to capture the interest of the American audience in 1963 and 1967 with Astro Boy and Speed Racer respectively. This was the beginning of a long process of marketing and fan organisations illegally obtaining, translating and distributing VHS tapes and later laserdisc copies of anime.

“In 1963 a one-shot of the Astro Boy (1952) manga was translated into English by Gold Key Comics. Later in 1966 an anime adaptation of Tezuka’s Kimba the White Lion was released and won the St. Mark’s Silver Lion Award at the 19th Venice International Film Festival in 1967. Much of the manga (very limited) and anime that were available in the US in the 1960’s was from Osamu Tezuka.”

Manga was almost unheard of in American in the 1960’s. Except for a limited amount of one-shot publications. Most of these were Osamu Tezuka’s work, such as Gold Key Comics translation of Astro Boy in 1963. I had to actively avoid discussing Osamu Tezuka as he had the largest role to play in manga and anime in Japan at the time. I could have gone into greater detail about the anime that was produced and even discussed other anime and what little translated manga was available. However, I think it was sufficient to only discuss the more popular manga and anime that broke into the market. This is due to the later impact and influence that series’ such as Astro Boy (1963), Speed Racer (1967), Kimba the White Lion (1965) and Panda and the Magic Serpent (1958) had on the American audience. Each of these not only caused the acceptability of anime on American screens, but these four anime also continued to influence American viewers well into the 1990’s. For example, as I mentioned in the post, Speed Racer was still relevant in 1997, as seen in the parody episode, Mock 5 of Dexter’s Laboratory (1996). Speed Racer even got a reboot anime with mixed success. The animation was updated and the themes and settings were changed to be more relevant to the youth of the late 1990’s. I am satisfied with this post for the most part. I accurately described the introduction of manga and anime in the 1960’s while using well known examples to help the reader understand the slow but important rise of both mediums.

I believe 1970’s: How Manga and Anime Was Consumed in the United States was a more in-depth look at the consumption of manga and anime. In this post, it was clearer how the fan organisations, the Japanese manga publishers, and anime producers pushed their products in the US. I think this post better exhibits the range of manga and anime available. I focused mainly on the fan groups and the influx of illegal copies of manga and anime that was available in L.A. and New York in the 1970’s.

“A major part of manga and anime fandom in the US was the availability of pirated copies and fan parties in large cities such as L.A. and New York. In 1976 an anime fan named Mark Merlino began taping obscure science fiction and fantasy films to show at fan parties. These parties eventually led to small screens such as the C/FO (Cartoon and Fantasy Organization) which was attended by Osamu Tezuka in 1977.”

This post describes how more mature anime was brought to American screens in the 1970’s. Even though Star Blazers was censored and cut down in episode numbers, it still captured children and teenagers interests. On the other hand, the late 1970’s was the real introduction of manga and anime to the US. There was a massive flood of manga and anime, in part due to fan organisations and comic conventions. This caused a rise in anime that did not hide its Japanese connections. I believe this post better describes the rise of manga and anime than the 1960’s post. There was far more information about the different types manga and anime and how they were translated and distributed in the 1970’s. However, I admit I could have structured my post more. I also think it would have been a good idea to write a post on the use of anime and American comics to promote toys in the US. Overall however, I am happy with this post. I feel I accurately documented the rise and the reasons surrounding manga and anime in 1970’s America .

There was a large shift in the view of manga and anime in the late 1980’s. This was in part due to Streamline Pictures, who dubbed and released a number of mature adult anime in the West. 1980’s: How Manga and Anime was Consumed in the United States focused on the sudden rise of manga and anime in the US. In the last few years I have turned to manga and anime from the 1980’s for entertainment. So much of it has influenced different areas of culture in the US. For example, Berserk (1986) is known for influencing the Dark Souls series (2011) which was universally praised in the US. I wrote this post due to some of these striking images. I had grown up on manga and anime from the 1990’s, now I had begun to turn even further back to understand where so much inspiration and various homages originated.

The interest of Japanese publishers and producers who pushed for English translations and brought their artists, writers, and works to comic conventions such as the San Diego Comic Con in 1980.

“The 1980 San Diego Comic Com was attended by over thirty Japanese cartoonists, including Osamu Tezuka, Go Nagai and Yumiko Igarashi. This was also the first year that had several anime cosplayers in its Masquerade (a pantomime with video game, comic, film and cartoon characters).”

There is a great quote from the vice president of Cartoon Network in 1997. He stated that “our children are safe because anime is not shown on American TV” (Patten Watching Anime 108). That line always made me laugh considering Cartoon Network was the home of Toonami and English translated anime in the West. Even the CEO of Disney publicly stated that Studio Ghibli was not anime studio, it was just an animation studio that happened to be Japanese. As anime was only childish, violent and mindless. When asked about the anime Speed Racer, both executives retorted that it could not be anime as it was too good. It is strange to me, who never questioned the value of anime that there was this misconception that anime was not to be taken seriously. The first anime to truly break that idea was Akira (1988), when it was released in the US in 1989.

“One of the more important anime films to be produced was Akira in 1988. It was subbed and dubbed into English in 1989 and was the first mature anime to be theatrically released… The film gained critical acclaim, even though the plot was muddled and too long. The high production value was what drew an audience to the theatres, along with its gritty violence and graphics. Another important aspect was that it was nothing like anything that had been previously seen in the US as it was not aimed at children.”

But due to a less than stellar translation, the anime was again seen as just mindless violence. I think this entry feels rushed overall due to the amount of content that was at my disposal. I believe I could have offered more analysis of the reasons for the success of manga and anime in the US. However, this was still a period where both were seen a trivial. I think in this post I successfully discussed how manga and anime gained more popularity, but I could have delved deeper into one or two of my examples more. However, this final post does show a significant improvement in my blogging, writing and descriptive abilities when compared to my first post.

In this review of my own blog, I did of course find plenty to criticize, I also found plenty to be proud of. I could have given more this blog more if I had the foresight to plan my entries better. As this blog continued to expand I know I felt more comfortable writing about my interests, which I know have generally been seen as childish. Because of this blog, I am far more comfortable writing academically online. I know that I made plenty of grammar, punctuation, and other mistakes throughout my blog. I deem however, that I have improved greatly since my first post back in October. I feel that I tried to branch out in my subject matter, ranging from American comics, video games, censorship and of course manga and anime. Hopefully this will not be my last time blogging, I may continue posting about my thesis difficulties and discoveries during the summer.

Work Cited

Dragon Ball Z. Dir. Daisuke Nishio. Toei Animation, 1989. DVD.

Fitzgerald, Sarah. “1960’s: How Manga and Anime was Consumed in the United States.” Web log post. sarahfitz374, WordPress, 15/03/2016. 25/03/2016. Web.

Fitzgerald, Sarah. “1970’s: How Manga and Anime was Consumed in the United States.” Web log post. sarahfitzgerald374, WordPress, 24/03/2016. 25/03/2016. Web.

Fitzgerald, Sarah. “1980’s: How Manga and Anime was Consumed in the United States.” Web log post. sarahfitzgerald374, WordPress, 25/03/2016. 27/03/2016. Web.

Fitzgerald, Sarah. “Censorship in Ireland and Abroad.” Web log post. sarahfitzgerald374, WordPress, 14/03/2016. 25/03/2016. Web.

Fitzgerald, Sarah. “Crowdsourcing – Not as Fun as Crowdsurfing.” Web log post. sarahfitzgerald374,Wordpress, 30/11/2015. 24/03/2016. Web.

Fitzgerald, Sarah. “How important is the comic creator to the audience?” Web log post. sarahfitzgerald374, Wordpress, 01/11/2015. 26/03/2016. Web.

Fitzgerald,Sarah. “Wikipedia edit-a-thon: EditWikiLit.”. Web log post. sarahfitzgerald374, WordPress, 04/02/2016. 28/03/2016. Web.

Mathews, Janina. Mecha’s Apocalypse : The Significance of the Mechanoid in Japanese Post Apocalyptic Science Fiction Anime. Thesis. University College Cork, 2009. Print.

Nakazawa, Keiji. Bearfoot Gen. Tokyo: Shueisha, 1973. Print.

Napier, Susan J. From Impressionism to Anime: Japan as Fantasy and Fan Cult in the Mind of the West. New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2007. Print.

Nobelman, Marc. Bill the Boy Wonder: The Secret Co-Creator of Batman. Watertown: Charlesbridge Publishing (2012) Print.

Patten, Fred. Watching Anime, Reading Manga: 25 Years of Essays and Reviews. Berkeley: Stone Bridge Press, 2004. Print.

Schmidt, F.A. “The Good, The Bad and The Ugly: Why Crowdsourcing needs Ethics”. Cloud and Green Computing (CGC), 2013 Third International Conference on (2013) Print.

Schodt, Frederik. Dreamland Japan Writings on Modern Manga. Berkelery: Stone Bridge Press, 1996. Print.

Toriyama, Akira. Dragonball. Tokyo: Shueisha, 1985. Print.